Close Encounters

in Time of War

A German countess learns how her father, briefly commander of German forces on Paros during World War II, and Abbot Philotheos of Longovardas Monastery, now recognized as a saint, spared the lives of 125 Parians in July 1944.

by Katherine Clark

Monday, February 26th, 2024, at 19:00

At the Municipal Arts Centre (Dimitrakopoulos Blg)

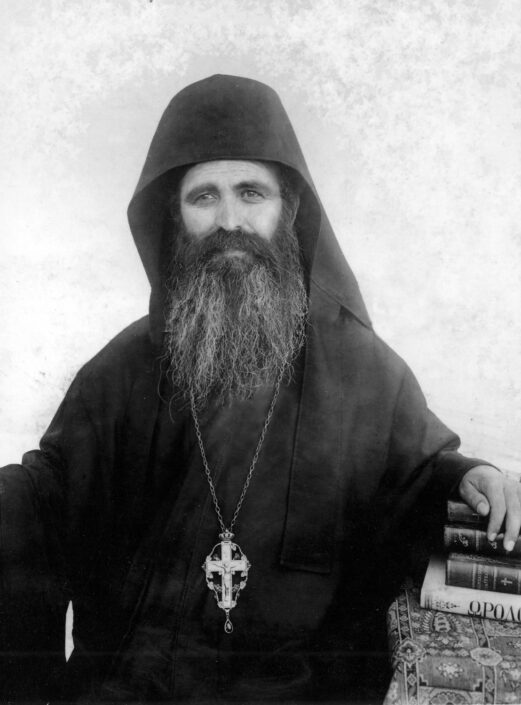

An extraordinary meeting, in the spring of 1944, between Abbot Philotheos Zervakos of Longovardas monastery and a German commanding officer averted the execution of 125 Parians who had been resisting the Nazi occupation. Katherine Clark, the author of The Orthodox Church, a Simple Guide and The Part that is Great, offers us a vivid and gripping account of this episode and of Parian bravery and resistance in WWII.

Katherine Clark

Closing the Circle

In 1944, Paros was occupied by German forces, which had taken over from the Italians. Their purpose on Paros was to build an airfield on the plain of Gallios near the villages of Prodromos (formerly Dragoulas), Marmara and Marpissa (formerly Tsipidos). Strategically, this was an important undertaking, since Paros was well placed for the defence of the entire Aegean and its shipping routes. Hundreds of men from Paros, Antiparos and Naxos worked on the large German project. The Allies — particularly the British — did everything they could to stop it, working with local partisans.

On 16 May 1944, an English submarine landed near Tripiti, discharging commandos under the Danish captain Andrea Lassen. Joining with local partisans, in Marpissa they severely wounded German Airfield Commander Tabel, and in Prodromos they killed two German radio operators. They surprised seven German soldiers in their sleep took them prisoner and cut all power and telephone lines to the airfield. At the airfield site, the Germans captured Parian partisan Nikolas Stellas, a 23-year-old from the mountains near Aghios Theodoros. He staunchly withstood all interrogation and refused to reveal the names of his comrades or other information about the operation. As a result, he was publicly hanged as a grim warning to other would-be partisans. His heroism is celebrated in Marpissa every year on a Sunday in May.

In line with German military policy at the time, reprisals were ordered: 125 Parians were to be selected by village leaders and executed, a dreadful blow anywhere at any time, and on little Paros, with few able-bodied men left on the island during the war, a disaster of staggering proportions. It fell to Major Georg Graf (Count) von Merenberg, Tabel’s successor as commander of airfield operations and German troops on Paros, to carry out the execution.

Von Merenberg was an unusual man. On his mother’s side, he was descended from Russian aristocracy, with Tsar Alexander II among his forebears, and the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. On his father’s side, he came from a German military family of the old school. He despised and abhorred the crude upstart Nazis and their brutal, lawless ways and never hesitated to let them feel it. He had had to defend himself twice before military tribunals: once for failing to use the Hitler salute, once for striking a Nazi party member to the ground.

The reprisal system — the execution of large numbers of non-combatants in revenge for the killing of any German soldier — revolted von Merenberg. His own credo was decency within the German military tradition of self-discipline, courage, honesty and obedience to superiors, combined with gallantry, humanity and civilized conduct toward non-combatants. An officer might be severe but not cruel, kill in battle but not murder. When still a captain in Russia during the winter of 1941 to 1942, at great personal risk he saved the lives of three young airmen who were to be shot for complaining about the quality of their winter clothing and equipment and making jokes about Hitler and Mussolini.

Von Merenberg was persona non grata with the Nazi high command, in his file a moratorium on promotion and denial of military pension. Still, as a capable officer and trained Luftwaffe pilot, he was just the man to supervise construction of an airfield on Paros in the Aegean, well out of the way of the mainstream of the war where fellow-officers were making their careers. He was a big, handsome man — 195 cm (6’ 5”) tall with finely-chiseled features in a severe countenance.

Nevertheless: whatever his feelings about reprisals, von Merenberg clearly had to obey orders and carry them out. These came direct from Hitler himself. Officers who did not were to be shot.

Representatives of the Paros and Antiparos villages, the clergy and other prominent Paros citizens, including Philotheos Zervakos, abbot of the monastery of Longovardas, formed a small group to plead for the lives of the 125 condemned Parians. They discreetly presented their problem to one of von Merenberg’s staff, Lieutenant Zasse, who told them officially there was little hope, that von Merenberg’s mind was made up. Nevertheless, unofficially, he mentioned just as they were leaving his office that they might try inviting the commander to visit Longovardas Monastery, where discussion might be easier, less official. It is important to understand the significance of this tip for the ultimate turn of events. For von Merenberg to negotiate with mayors or other political representatives of an occupied population would have been tantamount to treason. But there could be no objection from the German high command to his visiting the monastery and chatting with its abbot. Von Merenberg was a cultured man, with an interest in local customs, architecture, art and history — and a Russian Orthodox mother.

Abbot Philotheos lost no time in extending his invitation, and von Merenberg arrived early the next morning, Sunday 23 July, with an entourage of six officers and soldiers and an interpreter. Von Merenberg seemed distant, severe and imperious. Still the monks received their German visitors with true Greek hospitality and Christian kindness. After taking their guests on a tour of the library, the icon-painting gallery and the book bindery, they invited them to join them in the refectory for a meal. Under the extraordinary circumstances of this crucial visit, an exception was made to the monastery rule prohibiting meat, and in addition to the monastery’s fine cheeses, olives, figs, conserves and dark red wine, lamb was served — a rare treat amid the wartime shortages in any case.

The commander warmed to this hospitality and to the gentle friendliness and courtesy of the monks. He expressed his admiration for their ascetic lives, self-discipline, industriousness and kindness, and for the quiet serenity of the monastery. He appreciated their manner of taking their meal with their heads bowed as a reader read to them from spiritual texts. The patriarchal countenances of the elder monks particularly affected him. Little by little, he relaxed and became more approachable, less the military officer and more the man. The relationship between him and the abbot warmed: the abbot recounts that toward the end of the visit they had in fact become friends.

The commander and his entourage then attended the esperino (evening) service, where the monks prayed for the 125 condemned and for all those present in the chapel. Afterwards, they and their German guests assembled for coffee and spoon sweets, as was the custom.

At this point something wholly unexpected occurred. Amid the icons and portraits of former abbots in the reception room hung a painting of a seacoast village. Two Russian monks had brought it to Paros after the Russian Revolution, upon the dissolution of their monastery. Von Merenberg inspected this picture closely and at length. He then declared to the astonished monks that it was none other than his mother’s home village of Yalta (from the Greek yialó: Yalta was founded by Greek colonists in ancient times) in the Crimea on the Black Sea.

“You have no idea how this moves me,” he told them. “This is where I spent my summers during my childhood — a very happy time.” During these visits he must surely have attended Orthodox services with his Russian mother and grandmother — family marriages and baptisms and funerals, the liturgy on Sundays. Naturally, these profound memories of his childhood encounters with Orthodoxy would have given him an uncommon sensitivity to the Orthodox spirit of the monastery. Abbot Philotheos later recounted that at that point “the atmosphere around us filled with peace and goodwill. I felt within me that we had entered the realm of the miraculous.” The time had come to broach the subject of the 125 condemned.

As the abbot considered how to begin, the commander rose to take his leave. He thanked the abbot warmly for his hospitality. Well-mannered as he was, he offered to help the monastery in any way he could — to grant any favor the abbot asked. Abbot Philotheos took heart. He sent everyone out of the room but the interpreter, a fellow monk. Then he thanked the commander for his kind offer, but asked that he first promise he would indeed grant the favor, whatever it might be. The commander gave him his right hand and assured him he would. Whereupon the abbot begged that the lives of the 125 be spared.

“That cannot be,” said von Merenberg. “I, too, believe it is unjust, but it is not in my power to decide. I have orders from my superiors. If I do not obey them, I shall be executed myself. Ask me something else.” The abbot replied, “Be that as it may, since you promised the favor, you must keep your word. Take me instead of the 125.” Again the commander refused, saying that that would accomplish nothing. Still the abbot did not relent. “I must insist,” he said. “At least grant me a personal favor and include me among those to be executed.”

The two men faced each other, the abbot deadly serious, his face a map of his agony, tears filling his eyes. Von Merenberg was much moved — by the abbot’s feelings and plea, the monastery experience, the painting and the echoes of his childhood evoked in this closely related setting. Still, he faced a profound dilemma: To obey orders like a good soldier or to safeguard civilians like a true officer; to obey and violate his principles or to disobey and be shot.

At heart, of course, von Merenberg and the abbot agreed: Both sought the same outcome. The difficulty was how to achieve it. There at Longovardas in the “realm of the miraculous,” a solution presented itself. “I will spare their lives,” said von Merenberg, “but on one condition: You must see that the islanders do not engage in further sabotage. If they do, I shall be remorseless.” The abbot agreed and promised. He also blessed the commander, praying that the Holy Virgin of the Life-Giving Spring, patroness of the monastery, would watch over him and his family forever. Thus the commander left the monastery in peace, rescinded the order for execution and spared the 125.

The two men acted wisely. Von Merenberg’s decision was courageous and merciful. But it was also politic. To execute the 125 would have aroused implacable hatred among the local population, who would have been more intractable, rebellious and dangerous than ever. The abbot of Longovardas Monastery, that pivotal weathervane of Parian feeling and spiritual life at the time, embodied a unique opportunity for compromise — one the commander could not risk with village political leaders. He could rest more or less assured that the sabotage would stop and he could get his airfield built. There were no SS units on Paros to check on him. The Germans were losing the war. Hitler was facing disaster. An attempt had been made on his life only days before the count’s visit to the monastery. In Berlin the leadership had more serious considerations than events on an obscure island in the Cyclades. Hitler’s aides might not even have mentioned an act of insubordination that would infuriate him.

The abbot wisely bided his time, waited for the right moment, showed the German commander the good work and discipline of the monastery, its independence and the fruits of its labor. He allowed the gentle, sober demeanor of the monks and the hallowed monastery precincts to cast their spell on the hearts and minds of their German visitors. He let the knowledge of what was right in a deeper sense take hold of his German guest. He exposed von Merenberg to the great power of that Christian kindness “which can tame even wild beasts.” He put his faith in the Virgin protectress of his monastery to devise a good outcome, and his faith was rewarded.

The feelings of Germans visiting the monastery during 1944 are expressed in their remarks in the visitors’ book that the monastery preserves to this day. Entries in the visitors’ book also make clear that Graf von Merenberg was relieved of his command soon after these events — very probably for disobeying orders.

The intervention of the Holy Virgin of the Life-Giving Spring at the monastery dedicated to her, her gracious presence as the wellspring of wisdom and goodness, and her granting of insight and guidance to Abbot Philotheos Zervakos led in 2006 to his being recognized as a saint. He is celebrated on 23 July, the anniversary of the date of the visit in 1944 by the German officers.

Postscript, April 2010

Knowing that I live in Germany, monks at Longovardas asked me to try to locate Graf Georg von Merenberg. It was difficult. Even the name “von Merenberg” was uncertain, being written in Greek letters or scrawled German handwriting and subject to numerous spelling variations. I wrote to several German military records offices without success. Finally a German friend who had visited Paros found the family in lineage records of the German nobility. As it turned out, the Graf had died in Wiesbaden in 1965, but his daughter, Dr Clotilde von Rintelen, Gräfin (Countess) von Merenberg, was still alive, married with three sons and living and practising psychiatry in Wiesbaden, near where I live.

With some trepidation, I telephoned these aristocratic strangers with my wild tale of Graf von Merenberg, the monks, the war on a remote Greek island sixty-six years before, the averted mass execution, the glorification of Abbot Philotheos Zervakos. The countess was much moved. It was the first she had heard of it. She knew only that her father had been on Paros and Naxos during the war — not even that he was there to build an airfield. He never spoke of his wartime activities. German officers’ families live to this day in dread that their fathers or grandfathers may have done horrible things during the war. What a joy, then, for this family to learn that their father’s wisdom and courage had saved lives under the terrible conditions of war — that his encounter with the monastery on Paros had led to the recognition of its abbot as a saint!

The von Rintelens invited me to visit at once and couldn’t have been more friendly and hospitable. They told me family stories, showed me old photos and gave me as much information as they could about their father/grandfather. Most of what I relate about von Merenberg is thanks to their information.

There are basically two stories here. It is a challenge to do justice to both. The sceptics say the Graf and the abbot were political and clever. Certainly there was clever engineering of events on both sides. Believers say the Virgin guided them both to a good outcome in response to the prayers of the faithful. Certainly there is evidence of this as well. “Coincidence is when the Good Lord chooses to remain incognito,” said Albert Schweitzer. I personally see no conflict here and hope I have combined the two interpretations without appearing naive to the sceptics or faithless to the faithful!

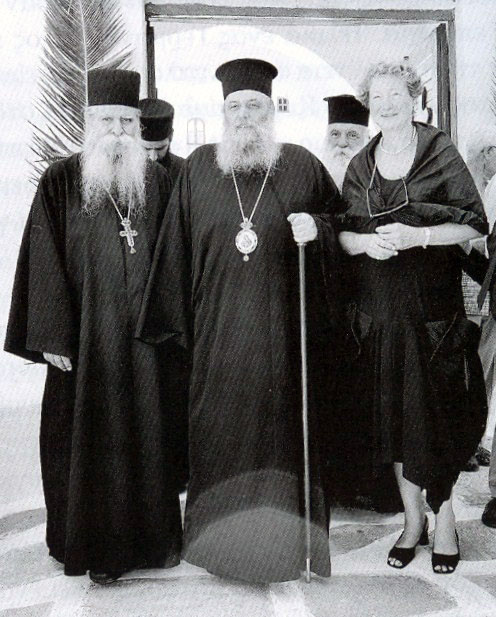

The countess and her husband, Dr Enno von Rintelen, visited Paros in May of 2010. On 30 May, at the memorial service for Nikolas Stellas in Marpissa, the Countess, wearing black and visibly moved, laid a bouquet of lilies and roses before the statue of Nikolas as an expression of solidarity with the Parians and what they suffered during the war and the profound sorrow she and her family feel that Germans had been responsible for the execution of that heroic youth. She returned to Paros with her sons on 23 July to attend the celebrations for Aghios Philotheos at Longovardas Monastery. And thus the circle closed in peace and goodwill, sixty-six years after these extraordinary events.

© 2010 Katherine Clark

Sources:

Interviews with Dr Clotilde von Rintelen, Dr Enno von Rintelen and their sons Alexander and Nicolaus, April 2010.

Longovardas Monastery calendar, 2006.

Article by Panayiotis Tsigonias, July to September 2005 edition of Spiritual Ark, a publication of the Church of the Ekatontapyliani in Paros.